"Knight Thoughts" - exclusive web content

Bruce Weber's remarkable dream poem to jazz's beautiful and damned master of cool, Chet Baker, returns to haunt again

Lé Jazz Cool:

Let's Get Lost

3-14-08 "Knight Thoughts" web exclusive review

By Richard Knight, Jr.

Let's Get Lost

3-14-08 "Knight Thoughts" web exclusive review

By Richard Knight, Jr.

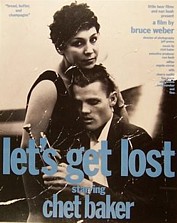

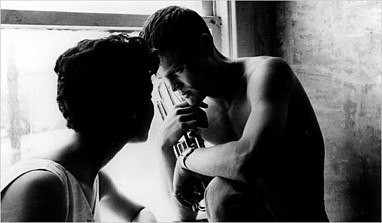

Let’s Get Lost, the 1989 documentary by über fashion photographer Bruce Weber about Chet Baker, jazz’s poster boy for the

beautiful and the damned opens at Chicago's Music Box Theatre this Friday, March 14 with a new 35mm print. Shot in sultry, dreamy

black & white, Weber’s visual postcard contrasts the handsome Baker of the 50s crooning "My Funny Valentine” and playing a

sensual, lethargic trumpet with the caved in, nearly comatose 58 year-old junkie of 30 years on. Weber intersperses the vintage

footage of Baker (on the Steve Allen show, for example and in rare brief movie appearances) with the man that Baker had become

nearly 30 years after his first flush of fame. Here we see the effects of the long disconnection from reality: the beautiful face

smashed in (Baker's teeth were famously knocked out in the early 70s nearly costing him what was left of his career), a man barely

responding to questions, fixated on lighting another cigarette, and living in the moment.

Much of the new footage features Baker in Santa Monica, California riding around in a Cadillac convertible packed between a group of

beautiful and overenthusiastic hipsters that include Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Chris Isaak and some gorgeous brunette

models. Though Weber would have one see the inclusion of these folks as a natural continuation of Baker's cool persona (jazz

passengers on the same train as it were) I found their presence irritating and insulting though Baker, drugged out and rarely

engaged, seemed not to notice them. Wedged between them in the Cadillac with its giant fishtail fins he looks straight ahead or

into the eyes of his then love interest. In a sequence where the group cavorts in bumper cars Baker again takes no notice of their

antics – rather, they are like pesky flies buzzing around the master. I had the same reaction when I first saw the film and brushed

them aside this time as surely as Baker must have - especially when he takes to the mic in the recording studio. At that point, any

idea that he would be diverted by this gaggle of enforced hanger-ons who seem to know nothing of jazz and ask idiotic questions

(which he quickly dismisses) dissipates.

When Baker begins to engage with the music we at last get a chance to connect the young sultry Baker with this man with the caved

in face. His voice, just above a whisper, can seem to barely summon the energy to get the love ripened lyrics out yet there is no

doubt that we are watching and listening to a master at work. To watch Baker sing and play remains spellbinding. All that self-

inflicted damage hadn’t dimmed a whit of his effortless musical genius. Later, when the group visits the Cannes Film Festival and

Baker sings in a club, he angrily refuses to do an encore, pissed that it’s not a jazz audience. And was he right. When he then

performs “Almost Blue” he entreats the audience to pay him the respect he’s entitled to and the performance is again sheer Baker

magic.

It’s not hard to understand Weber’s initial motivation in making the film (which was nominated for an Oscar in the documentary

category). As the retro footage and vintage photographs point out all too clearly, to see the young Baker, with his Narcissus like

beauty, combined with all that musical talent, would have been an overwhelming experience for any young artistic dreamer stuck in

the repressed 50s (Weber says as much in a voice over when he relates how he fixated on an album cover of the young hunk).

Interestingly enough, there’s little commentary on Baker’s extraordinary good looks – or much about his dual appeal to women and

homosexual men. Certainly, Baker’s movie star looks were the entry point for a thousand daydreams (still are) and I wish Weber,

who famously and almost single handedly pushed fashion photography back toward the idealized 50s dreamboat that Baker

epitomized, had stressed this point. Weber’s initial enthusiasm for Baker had everything to do with those Marlon Brando meets

Monty Clift meets James Dean looks (as he comments) but perhaps he decided that audiences would make the connection

themselves by just seeing the young and mesmerizing Baker (it certainly made the point for me).

Alternately tart and wistful interviews with the jazz legend’s mother, one ex-wife, an ex-girlfriend (the brassy, funny and supremely

talented Ruth Young) and three of his four children (who got his looks) round out Weber’s dreamy tone poem. Baker (who died

from a fall out of a hotel window most likely during a drug induced haze before the film was released) was obviously no picnic to live

with (what genius is?) but even among his ex-lovers there’s a grudging acceptance that once under Chet’s spell, always under it.

Let’s Get Lost is a beautiful film – as flawed as its subject, and all the more fascinating because of its odd lapses. Rarely seen since

its initial release and not available on DVD, it remains a cogent example of one man’s blatant objectification of another. There have

been few visual valentines as lush and pervasive as this – Weber’s love letter to Baker’s haunting beauty and out of this world

musical talent continues to resonate so deeply because both were so senselessly, mysteriously thrown away.

beautiful and the damned opens at Chicago's Music Box Theatre this Friday, March 14 with a new 35mm print. Shot in sultry, dreamy

black & white, Weber’s visual postcard contrasts the handsome Baker of the 50s crooning "My Funny Valentine” and playing a

sensual, lethargic trumpet with the caved in, nearly comatose 58 year-old junkie of 30 years on. Weber intersperses the vintage

footage of Baker (on the Steve Allen show, for example and in rare brief movie appearances) with the man that Baker had become

nearly 30 years after his first flush of fame. Here we see the effects of the long disconnection from reality: the beautiful face

smashed in (Baker's teeth were famously knocked out in the early 70s nearly costing him what was left of his career), a man barely

responding to questions, fixated on lighting another cigarette, and living in the moment.

Much of the new footage features Baker in Santa Monica, California riding around in a Cadillac convertible packed between a group of

beautiful and overenthusiastic hipsters that include Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Chris Isaak and some gorgeous brunette

models. Though Weber would have one see the inclusion of these folks as a natural continuation of Baker's cool persona (jazz

passengers on the same train as it were) I found their presence irritating and insulting though Baker, drugged out and rarely

engaged, seemed not to notice them. Wedged between them in the Cadillac with its giant fishtail fins he looks straight ahead or

into the eyes of his then love interest. In a sequence where the group cavorts in bumper cars Baker again takes no notice of their

antics – rather, they are like pesky flies buzzing around the master. I had the same reaction when I first saw the film and brushed

them aside this time as surely as Baker must have - especially when he takes to the mic in the recording studio. At that point, any

idea that he would be diverted by this gaggle of enforced hanger-ons who seem to know nothing of jazz and ask idiotic questions

(which he quickly dismisses) dissipates.

When Baker begins to engage with the music we at last get a chance to connect the young sultry Baker with this man with the caved

in face. His voice, just above a whisper, can seem to barely summon the energy to get the love ripened lyrics out yet there is no

doubt that we are watching and listening to a master at work. To watch Baker sing and play remains spellbinding. All that self-

inflicted damage hadn’t dimmed a whit of his effortless musical genius. Later, when the group visits the Cannes Film Festival and

Baker sings in a club, he angrily refuses to do an encore, pissed that it’s not a jazz audience. And was he right. When he then

performs “Almost Blue” he entreats the audience to pay him the respect he’s entitled to and the performance is again sheer Baker

magic.

It’s not hard to understand Weber’s initial motivation in making the film (which was nominated for an Oscar in the documentary

category). As the retro footage and vintage photographs point out all too clearly, to see the young Baker, with his Narcissus like

beauty, combined with all that musical talent, would have been an overwhelming experience for any young artistic dreamer stuck in

the repressed 50s (Weber says as much in a voice over when he relates how he fixated on an album cover of the young hunk).

Interestingly enough, there’s little commentary on Baker’s extraordinary good looks – or much about his dual appeal to women and

homosexual men. Certainly, Baker’s movie star looks were the entry point for a thousand daydreams (still are) and I wish Weber,

who famously and almost single handedly pushed fashion photography back toward the idealized 50s dreamboat that Baker

epitomized, had stressed this point. Weber’s initial enthusiasm for Baker had everything to do with those Marlon Brando meets

Monty Clift meets James Dean looks (as he comments) but perhaps he decided that audiences would make the connection

themselves by just seeing the young and mesmerizing Baker (it certainly made the point for me).

Alternately tart and wistful interviews with the jazz legend’s mother, one ex-wife, an ex-girlfriend (the brassy, funny and supremely

talented Ruth Young) and three of his four children (who got his looks) round out Weber’s dreamy tone poem. Baker (who died

from a fall out of a hotel window most likely during a drug induced haze before the film was released) was obviously no picnic to live

with (what genius is?) but even among his ex-lovers there’s a grudging acceptance that once under Chet’s spell, always under it.

Let’s Get Lost is a beautiful film – as flawed as its subject, and all the more fascinating because of its odd lapses. Rarely seen since

its initial release and not available on DVD, it remains a cogent example of one man’s blatant objectification of another. There have

been few visual valentines as lush and pervasive as this – Weber’s love letter to Baker’s haunting beauty and out of this world

musical talent continues to resonate so deeply because both were so senselessly, mysteriously thrown away.