Knight at the Movies Archives

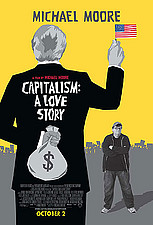

Michael Moore and Jane Campion return

All the familiar hallmarks are there: the contrast between the vintage, archival footage of the halcyon days of yore with its perky

music and jokey narration and the brutal realities of today with its ironic voice over, the black comedy stunts, the unearthed, telling

documentary footage. Then there are the jaw dropping stories of the little guy caught up in the uncaring system, the bottom feeders

getting rich on the economic woes of the disenfranchised, examples of indifference on the part of the rich and politically powerful, the

sobering facts and figures, the breathless malfeasance.

Finally, the big shambling guy himself wanders into view, bullhorn in hand and the reason for the sense of déjà vu that overwhelms

Capitalism: A Love Story, Michael Moore’s new film, from its opening moments clicks firmly into place. Here is Moore’s return to

the themes that put him on the map with Roger & Me, his film about the devastation of his hometown Flint, Michigan by the

indifferent auto industry. It’s we vs. them, the great unwashed vs. the microscopic but exceedingly rich and powerful, the overriding

taint of corruption and wealth bearing down on the easily distracted masses, the lone voice crying out against wrongdoing. 20 years

later, as Moore points out persuasively, the economic decimation and emotional despair of Flint has spread to our entire country.

Moore has taken on the Bush administration (Fahrenheit 911), the gun lobby (Bowling for Columbine), the health care industry (Sicko)

and now goes after what may be his biggest target – Wall Street. In examining the financial sleight of hand practiced by what are

essentially a group of high end gamblers, Moore has made what may be his magnum opus. This one time “little guy” who has

become a touchstone for a generation of underserved lefties speaks for us and to us in a style and manner that has taken him from

his humble beginnings to the world’s most powerful filmmaker. Ironically, this time when Moore returns to GM headquarters in Detroit

repeating a stunt he attempted in Roger & Me, the place is bankrupt, no longer the profitable lodestone it once was.

Greed is definitely not good in Moore’s view. He jauntily begins his latest film polemic with excerpts from an educational movie

about the fall of ancient Rome (Cheney, naturally, is cast as the evil emperor of this realm). He points the finger at Wall Street,

beginning with the Reagan presidency and deregulation of the industry (along with a lowering of the tax code for the rich). Reagan,

the former actor and shill for corporate America, is seen as the dummy front man for Wall Street/corporate America and Moore offers

a stunning clip of Reagan’s Chief of Staff and Secretary of the Treasury Don Regan telling the President while addressing Wall Street

to “speed it up.”

“Who tells the President to speed it up?” Moore demands in voice over and he quickly proceeds to track the close relationship

between Wall Street and political power that has existed since. We see a lot of horrifying things done in the name of personal and

corporate greed – stuff like life insurance policies taken out on unaware employees (they’re referred to as “dead peasants”) – and

the devastating effect this has had on regular folks (who are shown at the outset narcotized by the modern day version of the arena

– reality shows – and distracted by true reality). By the time Moore gets to a Peoria farmer and his family being put out of their

fourth generation home (who are so strapped they have accepted $1,000 from the bank to get their house ready for the new owners)

one feels worn down.

Even the euphoria of the Obama election – seemingly the one bright spot in this morass (and the movie) – is fleeting and Moore

doesn’t really offer any solutions to our mess much beyond, “vote the bums out of office.” At the fade out even he seems ready to

call it quits: “I can’t do this anymore unless you in the theatre watching this join me” he says. But though this later day Don Quixote

has certainly tilted many a windmill off balance in his time one wonders what kind of impact his message has ultimately had. Many

times during the current debate over healthcare I’ve thought to myself, “If everyone in this country watched Sicko the discussion

would be over in seconds and we’d have healthcare for all.”

If only we could take Michael Moore out of the movie, that is. Because Moore is such a polarizing figure, the very people who need

to hear his warnings of catastrophe shut him out and the rest of us? I love him but I’m not sure that his alternately

entertaining/sobering documentaries have really had much of a cultural impact beyond the short term. This modern day Cassandra

has delivered yet another urgent warning for America but will anyone really listen once the movie is over? I felt truly heartsick at the

end of Capitalism: A Love Story – because it seems that on many levels the messenger has once again overwhelmed his insightful

message.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Writer-director Jane Campion, Oscar winner for The Piano, returns to a period romantic melodrama with Bright Star, the story of the

three year courtship between poet John “A thing of beauty is a joy forever” Keats (Ben Whishaw) and fashionista Fanny Brawne (Abie

Cornish). “Melodrama” is probably too lush a word to lob at this rather dry film that could have used a lot more juice. Though the

movie contains a feisty performance from Cornish, a somber one from Whishaw (what else to do with the gloomy Keats?) and a nice,

nasty one from Paul Schneider as Charles Armitage Brown, Keats’ best friend and fellow poet, Campion’s movie is as perfectly

composed as an intricate, exactingly detailed museum exhibit or one of those 16-hour Masterpiece Theatre adaptations of Dickens.

I wanted to love it because it’s so damn literary and exquisitely put together but ultimately it felt like a very long two hours.

The time is 1818 on the outskirts of London and Keats is sharing rooms with Brown, both of whom are boarding in the home of

Fanny’s mother. As Campion goes about setting up the romance there’s some nice cultural diversion in seeing how these folks

lived. Her eye for this kind of period detail is wondrous as always – the rows of white sheets flapping on a hillside, the detailed

stitching in a lacy collar, the male harmony choir at the party, the ritual of the party itself with its dance cards and intricate dances.

Campion has always had a particular feel for this world, the stuffy, repressed emotions of the Victorian era versus the restorative

powers of nature (a talent she shares with Terrence Malick) and we get a lot of that here (helped along by the lovely minimalist

music). But the romance, which blossoms slowly – very slowly – after an emotionally gorgeous scene in which Fanny stitches a pillow

slip to be placed in the coffin under the head of Keats’ dead brother – never catches hold. This isn’t just because Keats is a man of

no means or much station, as Fanny’s mother warns, but because Brown, the best friend, behaves like a jealous, petulant brat who

blocks the relationship at every turn – an annoyance that eventually supersedes the quasi-love affair (quasi because it’s never

consummated – Keats and Fanny only share a kiss here and there).

Though the relationship between Keats and Brown is clearly not homoerotic (Brown fathers a child with the maid who becomes his put

upon wife) Brown just feels intellectually, creatively superior to Fanny and Keats lets him take the upper hand. It seems that every

time the relationship will finally catch hold one can count on spoilsport Brown to throw in the kibosh. The movie really ends up less a

love story and more a bizarre love triangle.

Though Campion’s eye for period detail is diverting and some of the scenes pack an emotional wallop, ultimately Bright Star is a

highfalutin snore. Poetry and cultural aesthetes may champion Campion’s creative vision and I hung in there trying not to nod off

but honestly, my attention wandered until pretty much the second Keats started coughing, signaling the beginning of the end.

music and jokey narration and the brutal realities of today with its ironic voice over, the black comedy stunts, the unearthed, telling

documentary footage. Then there are the jaw dropping stories of the little guy caught up in the uncaring system, the bottom feeders

getting rich on the economic woes of the disenfranchised, examples of indifference on the part of the rich and politically powerful, the

sobering facts and figures, the breathless malfeasance.

Finally, the big shambling guy himself wanders into view, bullhorn in hand and the reason for the sense of déjà vu that overwhelms

Capitalism: A Love Story, Michael Moore’s new film, from its opening moments clicks firmly into place. Here is Moore’s return to

the themes that put him on the map with Roger & Me, his film about the devastation of his hometown Flint, Michigan by the

indifferent auto industry. It’s we vs. them, the great unwashed vs. the microscopic but exceedingly rich and powerful, the overriding

taint of corruption and wealth bearing down on the easily distracted masses, the lone voice crying out against wrongdoing. 20 years

later, as Moore points out persuasively, the economic decimation and emotional despair of Flint has spread to our entire country.

Moore has taken on the Bush administration (Fahrenheit 911), the gun lobby (Bowling for Columbine), the health care industry (Sicko)

and now goes after what may be his biggest target – Wall Street. In examining the financial sleight of hand practiced by what are

essentially a group of high end gamblers, Moore has made what may be his magnum opus. This one time “little guy” who has

become a touchstone for a generation of underserved lefties speaks for us and to us in a style and manner that has taken him from

his humble beginnings to the world’s most powerful filmmaker. Ironically, this time when Moore returns to GM headquarters in Detroit

repeating a stunt he attempted in Roger & Me, the place is bankrupt, no longer the profitable lodestone it once was.

Greed is definitely not good in Moore’s view. He jauntily begins his latest film polemic with excerpts from an educational movie

about the fall of ancient Rome (Cheney, naturally, is cast as the evil emperor of this realm). He points the finger at Wall Street,

beginning with the Reagan presidency and deregulation of the industry (along with a lowering of the tax code for the rich). Reagan,

the former actor and shill for corporate America, is seen as the dummy front man for Wall Street/corporate America and Moore offers

a stunning clip of Reagan’s Chief of Staff and Secretary of the Treasury Don Regan telling the President while addressing Wall Street

to “speed it up.”

“Who tells the President to speed it up?” Moore demands in voice over and he quickly proceeds to track the close relationship

between Wall Street and political power that has existed since. We see a lot of horrifying things done in the name of personal and

corporate greed – stuff like life insurance policies taken out on unaware employees (they’re referred to as “dead peasants”) – and

the devastating effect this has had on regular folks (who are shown at the outset narcotized by the modern day version of the arena

– reality shows – and distracted by true reality). By the time Moore gets to a Peoria farmer and his family being put out of their

fourth generation home (who are so strapped they have accepted $1,000 from the bank to get their house ready for the new owners)

one feels worn down.

Even the euphoria of the Obama election – seemingly the one bright spot in this morass (and the movie) – is fleeting and Moore

doesn’t really offer any solutions to our mess much beyond, “vote the bums out of office.” At the fade out even he seems ready to

call it quits: “I can’t do this anymore unless you in the theatre watching this join me” he says. But though this later day Don Quixote

has certainly tilted many a windmill off balance in his time one wonders what kind of impact his message has ultimately had. Many

times during the current debate over healthcare I’ve thought to myself, “If everyone in this country watched Sicko the discussion

would be over in seconds and we’d have healthcare for all.”

If only we could take Michael Moore out of the movie, that is. Because Moore is such a polarizing figure, the very people who need

to hear his warnings of catastrophe shut him out and the rest of us? I love him but I’m not sure that his alternately

entertaining/sobering documentaries have really had much of a cultural impact beyond the short term. This modern day Cassandra

has delivered yet another urgent warning for America but will anyone really listen once the movie is over? I felt truly heartsick at the

end of Capitalism: A Love Story – because it seems that on many levels the messenger has once again overwhelmed his insightful

message.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Writer-director Jane Campion, Oscar winner for The Piano, returns to a period romantic melodrama with Bright Star, the story of the

three year courtship between poet John “A thing of beauty is a joy forever” Keats (Ben Whishaw) and fashionista Fanny Brawne (Abie

Cornish). “Melodrama” is probably too lush a word to lob at this rather dry film that could have used a lot more juice. Though the

movie contains a feisty performance from Cornish, a somber one from Whishaw (what else to do with the gloomy Keats?) and a nice,

nasty one from Paul Schneider as Charles Armitage Brown, Keats’ best friend and fellow poet, Campion’s movie is as perfectly

composed as an intricate, exactingly detailed museum exhibit or one of those 16-hour Masterpiece Theatre adaptations of Dickens.

I wanted to love it because it’s so damn literary and exquisitely put together but ultimately it felt like a very long two hours.

The time is 1818 on the outskirts of London and Keats is sharing rooms with Brown, both of whom are boarding in the home of

Fanny’s mother. As Campion goes about setting up the romance there’s some nice cultural diversion in seeing how these folks

lived. Her eye for this kind of period detail is wondrous as always – the rows of white sheets flapping on a hillside, the detailed

stitching in a lacy collar, the male harmony choir at the party, the ritual of the party itself with its dance cards and intricate dances.

Campion has always had a particular feel for this world, the stuffy, repressed emotions of the Victorian era versus the restorative

powers of nature (a talent she shares with Terrence Malick) and we get a lot of that here (helped along by the lovely minimalist

music). But the romance, which blossoms slowly – very slowly – after an emotionally gorgeous scene in which Fanny stitches a pillow

slip to be placed in the coffin under the head of Keats’ dead brother – never catches hold. This isn’t just because Keats is a man of

no means or much station, as Fanny’s mother warns, but because Brown, the best friend, behaves like a jealous, petulant brat who

blocks the relationship at every turn – an annoyance that eventually supersedes the quasi-love affair (quasi because it’s never

consummated – Keats and Fanny only share a kiss here and there).

Though the relationship between Keats and Brown is clearly not homoerotic (Brown fathers a child with the maid who becomes his put

upon wife) Brown just feels intellectually, creatively superior to Fanny and Keats lets him take the upper hand. It seems that every

time the relationship will finally catch hold one can count on spoilsport Brown to throw in the kibosh. The movie really ends up less a

love story and more a bizarre love triangle.

Though Campion’s eye for period detail is diverting and some of the scenes pack an emotional wallop, ultimately Bright Star is a

highfalutin snore. Poetry and cultural aesthetes may champion Campion’s creative vision and I hung in there trying not to nod off

but honestly, my attention wandered until pretty much the second Keats started coughing, signaling the beginning of the end.

They're Back:

Capitalism: A Love Story-Bright Star

Expanded Edition of 9-30-09 Windy City Times KATM Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

Capitalism: A Love Story-Bright Star

Expanded Edition of 9-30-09 Windy City Times KATM Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

CHECK OUT OTHER KATM FILM REVIEWS IN THE ARCHIVES