Knight at the Movies Archives

Two offbeat indies that leave a trace

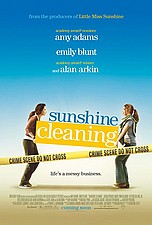

The team that produced the outsized indie hit Little Miss Sunshine have returned with another offbeat character study, Sunshine

Cleaning. The film stars the currently red hot Amy Adams and the versatile Emily Blunt (star of the lesbian romance My Summer of

Love and hysterically funny in The Devil Wears Prada). Adams and Blunt play Rose and Norah, two sisters who tentatively start a

business cleaning up after violent crime scenes as a way to climb out of their unsatisfied lives.

The picture, based on a first time script by Megan Holley (inspired by a segment from NPR’s “All Things Considered”) and directed by

Christine Jeffs (who also helmed the biopic Sylvie) has an unhurried pace and the same sort of gentle but tough quality of other

female centered pictures like Friends with Money and Housekeeping. It’s nicely observed, the characters feel true to life (Holley has a

telling eye) and the performances are uniformly excellent. But somehow the picture never quite catches hold; never really sinks in.

This may have to do with the over-familiarity of the leading arc of the story which follows Rose, a typical struggling young single

working mother. She’s the earnest sister, the hard worker who has taken some hard knocks and who can’t seem to let go of her

involvement with her now married high school sweetheart, a police detective (Steve Zahn, a wonder as always). It’s Rose who follows

up on the detective’s idea for her to start the business when she needs money to enroll her troubled young son in private school but

it’s her sister Norah, the ne’er do well, who is haunted by the crime scenes and can’t separate herself emotionally from them.

Though Rose’s story will tug at the heart strings and raise the hackles of many in the audience when she’s made to suffer a lot of

social indignities because she’s “just a cleaning woman” it was the screwed up Norah who resonated most with me. Norah, who can’t

hold a waitress job, prefers getting high and giving her little nephew nightmares with her violent bedtime stories, is funny and brash

but reveals enormous compassion when faced with the prospect of cleaning up the “crime scenes” which are more often than not the

aftermath of suicides. These are often found inside the cramped interiors of fetid trailers and beat up motel rooms, small

sanctuaries from the hot desert sunshine of Albuquerque where the action takes place. One crime scene in particular haunts Norah

and she tracks down the daughter (Mary Lynn Rajskub) of the victim, who thinks for a brief moment that Norah is interested in

romance

Rose and Norah themselves are both haunted by their own crime scene – the one they stepped into as little girls involving their

mother. Like the sisters Crimes of the Heart this incident has overshadowed their lives and set in stone their relationship – seemingly

implacable Rose has become adept at picking up after emotionally messy Norah but both are ticking time bombs. Alan Arkin plays

their eccentric father, a more benign version of the character he played in Little Miss Sunshine who has passed his gambler’s instinct

for the sell onto his grandson.

Though Sunshine Cleaning lacks the dramatic punch of Alice Doesn’t Live Her Anymore, the sweet daffiness of Waitress, the slapstick

wackiness of In Her Shoes, or the magic, ethereal quality of Housekeeping, it shares the same feminine spirit of empowerment

embodied in these movies. And like them, it takes the time to let us into the lives of even its most minor characters (Clifton Collins

Jr. from Capote, for example, is a marvel as the one-armed manager of the cleaning supply company who bonds with Rose’s son

over his model airplane hobby). Even with such a familiar story arc the characters in Sunshine Cleaning – both dead and alive – leave

behind vivid memories when the movie’s over. Invoking the idea of a feminine sensibility overhanging the movie isn’t meant to

demean the mostly good writing, acting, directing, and editing choices but rather to point out that this sensibility augments and

strengthens all of these. On that score, Sunshine Cleaning is a stellar example of feminist filmmaking.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

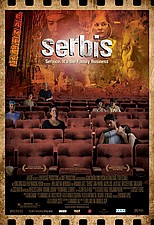

In the Filipino language the word Serbis means “Service” and that’s what the hustlers do to the male customers cruising them in the

run down movie theatre owned by the Pineda family in Brillante Mendoza’s enthralling film of the same title. The Pinedas, a rag tag

bunch ruled with an iron fist by the matriarch “Nanay Flor” (the marvelous Gina Pareno), are down to their last movie theatre and it’s

not much of a legacy. Beat up and run down, showing a succession of squalid porn films (with titles like “In Need of Joy”), the

movies are an excuse for the hustlers and their clientele to tryst on the second floor balcony, just below the family’s living quarters.

Though Nanay Flor has the final say it is her resigned daughter Nayda (Jacklyn Jose) who keeps everyone together and the theatre

running. But as the mother shuffles around the run down theatre, nagging the family’s two teenage boys to change the reels, fix the

leaking toilets, chastising her daughter to change out of too revealing clothes, and her small son to take a bath already, nothing in

the squalor seems to phase her – or the rest of the family either.

Set in Filipino city of Angeles, Mendoza’s film shows us a vivid portrait of a family seemingly involved in only their own problems who

have been infected by the filth and enervation around them. The seedy environment has crept into the soul of the family –

everyone seems tainted on some level by the ever present sex acts around them – although they pointedly ignore them and don’t

make the connection. Even the little boy is shown sporting red lipstick at one point and pedaling a tricycle through the congregation

of gay hustlers who go right on giving head to their customers as the kid pedals by.

In Mendoza’s nightmarish setting it’s always hot, steamy and noisy and the camera often shoots from on high. Everyone seems like

rats in a filthy, dark maze – especially when a goat wanders into the theatre momentarily interrupting the blow jobs and butt

fucking. You can feel the heat and smell the garbage and bad food in the place and like the teenage son who has impregnated his

girlfriend, you long for escape. The realistic but tragic solution the son comes up with, revealed at the fade out, simply adds a large

apostrophe mark to Mendoza’s insightful film. Plays exclusively at Landmark Century Centre Cinema. www.landmarktheatres.com

Cleaning. The film stars the currently red hot Amy Adams and the versatile Emily Blunt (star of the lesbian romance My Summer of

Love and hysterically funny in The Devil Wears Prada). Adams and Blunt play Rose and Norah, two sisters who tentatively start a

business cleaning up after violent crime scenes as a way to climb out of their unsatisfied lives.

The picture, based on a first time script by Megan Holley (inspired by a segment from NPR’s “All Things Considered”) and directed by

Christine Jeffs (who also helmed the biopic Sylvie) has an unhurried pace and the same sort of gentle but tough quality of other

female centered pictures like Friends with Money and Housekeeping. It’s nicely observed, the characters feel true to life (Holley has a

telling eye) and the performances are uniformly excellent. But somehow the picture never quite catches hold; never really sinks in.

This may have to do with the over-familiarity of the leading arc of the story which follows Rose, a typical struggling young single

working mother. She’s the earnest sister, the hard worker who has taken some hard knocks and who can’t seem to let go of her

involvement with her now married high school sweetheart, a police detective (Steve Zahn, a wonder as always). It’s Rose who follows

up on the detective’s idea for her to start the business when she needs money to enroll her troubled young son in private school but

it’s her sister Norah, the ne’er do well, who is haunted by the crime scenes and can’t separate herself emotionally from them.

Though Rose’s story will tug at the heart strings and raise the hackles of many in the audience when she’s made to suffer a lot of

social indignities because she’s “just a cleaning woman” it was the screwed up Norah who resonated most with me. Norah, who can’t

hold a waitress job, prefers getting high and giving her little nephew nightmares with her violent bedtime stories, is funny and brash

but reveals enormous compassion when faced with the prospect of cleaning up the “crime scenes” which are more often than not the

aftermath of suicides. These are often found inside the cramped interiors of fetid trailers and beat up motel rooms, small

sanctuaries from the hot desert sunshine of Albuquerque where the action takes place. One crime scene in particular haunts Norah

and she tracks down the daughter (Mary Lynn Rajskub) of the victim, who thinks for a brief moment that Norah is interested in

romance

Rose and Norah themselves are both haunted by their own crime scene – the one they stepped into as little girls involving their

mother. Like the sisters Crimes of the Heart this incident has overshadowed their lives and set in stone their relationship – seemingly

implacable Rose has become adept at picking up after emotionally messy Norah but both are ticking time bombs. Alan Arkin plays

their eccentric father, a more benign version of the character he played in Little Miss Sunshine who has passed his gambler’s instinct

for the sell onto his grandson.

Though Sunshine Cleaning lacks the dramatic punch of Alice Doesn’t Live Her Anymore, the sweet daffiness of Waitress, the slapstick

wackiness of In Her Shoes, or the magic, ethereal quality of Housekeeping, it shares the same feminine spirit of empowerment

embodied in these movies. And like them, it takes the time to let us into the lives of even its most minor characters (Clifton Collins

Jr. from Capote, for example, is a marvel as the one-armed manager of the cleaning supply company who bonds with Rose’s son

over his model airplane hobby). Even with such a familiar story arc the characters in Sunshine Cleaning – both dead and alive – leave

behind vivid memories when the movie’s over. Invoking the idea of a feminine sensibility overhanging the movie isn’t meant to

demean the mostly good writing, acting, directing, and editing choices but rather to point out that this sensibility augments and

strengthens all of these. On that score, Sunshine Cleaning is a stellar example of feminist filmmaking.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the Filipino language the word Serbis means “Service” and that’s what the hustlers do to the male customers cruising them in the

run down movie theatre owned by the Pineda family in Brillante Mendoza’s enthralling film of the same title. The Pinedas, a rag tag

bunch ruled with an iron fist by the matriarch “Nanay Flor” (the marvelous Gina Pareno), are down to their last movie theatre and it’s

not much of a legacy. Beat up and run down, showing a succession of squalid porn films (with titles like “In Need of Joy”), the

movies are an excuse for the hustlers and their clientele to tryst on the second floor balcony, just below the family’s living quarters.

Though Nanay Flor has the final say it is her resigned daughter Nayda (Jacklyn Jose) who keeps everyone together and the theatre

running. But as the mother shuffles around the run down theatre, nagging the family’s two teenage boys to change the reels, fix the

leaking toilets, chastising her daughter to change out of too revealing clothes, and her small son to take a bath already, nothing in

the squalor seems to phase her – or the rest of the family either.

Set in Filipino city of Angeles, Mendoza’s film shows us a vivid portrait of a family seemingly involved in only their own problems who

have been infected by the filth and enervation around them. The seedy environment has crept into the soul of the family –

everyone seems tainted on some level by the ever present sex acts around them – although they pointedly ignore them and don’t

make the connection. Even the little boy is shown sporting red lipstick at one point and pedaling a tricycle through the congregation

of gay hustlers who go right on giving head to their customers as the kid pedals by.

In Mendoza’s nightmarish setting it’s always hot, steamy and noisy and the camera often shoots from on high. Everyone seems like

rats in a filthy, dark maze – especially when a goat wanders into the theatre momentarily interrupting the blow jobs and butt

fucking. You can feel the heat and smell the garbage and bad food in the place and like the teenage son who has impregnated his

girlfriend, you long for escape. The realistic but tragic solution the son comes up with, revealed at the fade out, simply adds a large

apostrophe mark to Mendoza’s insightful film. Plays exclusively at Landmark Century Centre Cinema. www.landmarktheatres.com

Dirty Little Secrets & Lives:

Sunshine Cleaning-Serbis

Expanded Edition of 3-18-09 Windy City Times KATM Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

Sunshine Cleaning-Serbis

Expanded Edition of 3-18-09 Windy City Times KATM Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.