Knight at the Movies Archives

Todd Haynes returns with a superlative twist on the standard bio-pic, everything old is new only in terms of color in a predictable

African American holiday movie

African American holiday movie

Todd Haynes, the writer-director whose movie Poison kick started the queer film genre in the early 90s, is back with another

beautifully made film. I’m Not There is Haynes’ contemplative treatise “Inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan.” His

script (co-authored with Oren Moverman) about the elusive, mysterious folk hero whose life and career reached their apex during the

turbulent 1960s is a doozy. To tell his story, Haynes uses a battery of actors to play his leading man. Christian Bale, Perfume’s Ben

Whishaw, Heath Ledger, Richard Gere, Marcus Carl Franklin, and Cate Blanchett all take turns at aspects of the role. None are called

Bob Dylan in the movie (and Gere and Franklin actually play characters who inspired Dylan).

It’s a brilliant stroke – a biography that doesn’t ever mention its subject by name – and Haynes poetic audacity nearly carries the

day. Dylan’s story is viewed through the attitudes and visual signposts of the time in which he rose from idealistic cult figure to

superstar. The threads of his life and inspirations weave together throughout the movie. In one, Haynes gives us the offstage

Dylan (portrayed by Brokeback Mountain’s Ledger) through the ever distancing relationship of Dylan to his wife and children. In

another thread, Dylan’s fans are shocked when the strident folkie plugs in his guitar and with a literal boom; goes electric at an

outdoor folk festival, ignoring the taunts of the disbelieving crowd. This section, a visual send-up of A Hard Day’s Night (a funny sight

gag includes a nod to the Beatles) and D.A. Pennebaker’s concert tour film about Dylan, Don’t Look Back is sure to be the most

talked about part of the movie.

The reason for that is Blanchett’s mesmerizing turn as Dylan – it’s a dead on interpretation, down to the frizzy Harpo hairdo, the Ray

Bans, leather jacket, and incoherent mutterings. Blanchett, who last took Oscar gold for her Katharine Hepburn impersonation in The

Aviator, is sure to find herself among the nominees again for her audacious turn. The performance is not just a sleight of hand,

either. Haynes gives Blanchett the gift of Dylan at the height of his celebrity and his alternate embrace and denounce of it. It’s no

coincidence that the segment is filmed in black and white and is populated by the leering faces, persistent paparazzi, and long

tracking shots of Fellini. In paying homage to the maker of La Dolce Vita and 8 ½, Haynes creates another prism through which to

view Dylan and the celebrity culture he inspired (it also includes snippets of Dylan’s love for gay poet Allen Ginsberg and his odd

relationship with Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick). Throughout, we are constantly reminded that we are watching a movie; that its

folly to think that the real Dylan could ever be captured on film.

The other pseudo biographical section of the story isn’t nearly as successful. It’s told in the form of one of those Vh-1 “Behind the

Music” documentaries – a serious version of Christopher Guest’s folk music mockumentary A Mighty Wind and this thread (which

includes Julianne Moore and finds Christian Bale playing the Dylan character into his conversion to Christianity) is the weakest part of

the film and momentarily threatens to collapse Haynes’ delicate structure (it’s a very mannered, heavy-handed device much too

familiar to audiences to be taken seriously).

Other sections of the movie are mystical and poetic – drawing on Dylan’s influences and Haynes’ fascination with rebellion against

the constraints of rigid conservatism (a theme he also explored more literally in Far From Heaven). Dylan’s musical inspiration, folk

hero Woody Guthrie is envisioned in the person of a small African American boy (Marcus Carl Franklin) who hops freight cars and

totes around a beat up guitar until a black woman tells him to get with the times, prompting his switch to folk music activism. In

another segment Richard Gere plays the Wild West bandit Billy the Kid, whose individualism apparently inspired Dylan. Though the

link to Dylan isn’t clear it’s a beautifully filmed sequence that feels right.

The jigsaw puzzle approach of I’m Not There takes some getting used to and audiences steeped in traditional Hollywood structure are

going to probably find this non-linear film that leaves the moorings of traditional bio-pics far behind tough going. Plus, not all the

threads bind together (not that they’re actually meant to – that’s part of the point) but even with missteps (the mockumentary

segment with Bale and the stuff with the black kid in particular) Haynes takes you on a marvelous journey and its an intensely felt

picture that actually gets on the screen the enormous power that music in the hands of a genius can have on the world. There’s

never been a film quite like I’m Not There and even though it’s too long and gets a little too cow-eyed at times, Haynes’ unique

vision, the cinematic equivalent of the ultimate fan mail love letter, may be the precursor to an entirely new genre of poetic bio-pics.

That a potential new film genre has once again been initiated by a queer artist with the unique vision and tremendous gifts that

Haynes’ possesses isn’t a bit surprising. Want to see queer sensibility finely tuned to its height? Go see I’m Not There.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

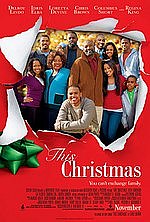

This Christmas, written and directed by Preston A. Whitmore II is standard issue holiday fare, Soul Food style in which Loretta

Devine presides over a family with lots of stereotypical problems returning to her California home at Christmas. I love Loretta

Devine, who should have gotten many more high profile movie roles after Waiting to Exhale (and plays a variation on that role here)

and am always happy to see her with another big screen part – even in a standard issue picture such as this. Regina King is the

oldest daughter who has taken on familial responsibility after the father left for good while Sharon Leal is the younger, beautiful and

selfish sister who went to New York for a modeling career. There’s an older brother on the lam from bookies, a younger brother who

is hiding the fact that he’s a talented vocalist, and a middle brother who is home for the holidays on leave from the Army and is

hiding a secret, too.

I’d forgotten that the trailer for the movie reveals the secret (he’s hooked up with a white woman) and was hoping things would get

interesting and that maybe he’d bring home his gay lover (talk about don’t ask/don’t tell!). But not a bit of it. All the characters

and their motivations are so stereotypical, in fact, that none of them really registers. On the plus side, inane as it is, at least this

isn’t one of those strident, slapstick white holiday movies – like Christmas with the Kranks – and also unlike its white counterparts, this

black holiday movie features gorgeous jazz versions of the Christmas standards and a sassy Soul Train line dance sequence (which

wears out its welcome, however, when Whitmore, who apparently loved it a lot, repeats it at the movie’s conclusion for a full five

minutes before rolling the credits).

beautifully made film. I’m Not There is Haynes’ contemplative treatise “Inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan.” His

script (co-authored with Oren Moverman) about the elusive, mysterious folk hero whose life and career reached their apex during the

turbulent 1960s is a doozy. To tell his story, Haynes uses a battery of actors to play his leading man. Christian Bale, Perfume’s Ben

Whishaw, Heath Ledger, Richard Gere, Marcus Carl Franklin, and Cate Blanchett all take turns at aspects of the role. None are called

Bob Dylan in the movie (and Gere and Franklin actually play characters who inspired Dylan).

It’s a brilliant stroke – a biography that doesn’t ever mention its subject by name – and Haynes poetic audacity nearly carries the

day. Dylan’s story is viewed through the attitudes and visual signposts of the time in which he rose from idealistic cult figure to

superstar. The threads of his life and inspirations weave together throughout the movie. In one, Haynes gives us the offstage

Dylan (portrayed by Brokeback Mountain’s Ledger) through the ever distancing relationship of Dylan to his wife and children. In

another thread, Dylan’s fans are shocked when the strident folkie plugs in his guitar and with a literal boom; goes electric at an

outdoor folk festival, ignoring the taunts of the disbelieving crowd. This section, a visual send-up of A Hard Day’s Night (a funny sight

gag includes a nod to the Beatles) and D.A. Pennebaker’s concert tour film about Dylan, Don’t Look Back is sure to be the most

talked about part of the movie.

The reason for that is Blanchett’s mesmerizing turn as Dylan – it’s a dead on interpretation, down to the frizzy Harpo hairdo, the Ray

Bans, leather jacket, and incoherent mutterings. Blanchett, who last took Oscar gold for her Katharine Hepburn impersonation in The

Aviator, is sure to find herself among the nominees again for her audacious turn. The performance is not just a sleight of hand,

either. Haynes gives Blanchett the gift of Dylan at the height of his celebrity and his alternate embrace and denounce of it. It’s no

coincidence that the segment is filmed in black and white and is populated by the leering faces, persistent paparazzi, and long

tracking shots of Fellini. In paying homage to the maker of La Dolce Vita and 8 ½, Haynes creates another prism through which to

view Dylan and the celebrity culture he inspired (it also includes snippets of Dylan’s love for gay poet Allen Ginsberg and his odd

relationship with Warhol superstar Edie Sedgwick). Throughout, we are constantly reminded that we are watching a movie; that its

folly to think that the real Dylan could ever be captured on film.

The other pseudo biographical section of the story isn’t nearly as successful. It’s told in the form of one of those Vh-1 “Behind the

Music” documentaries – a serious version of Christopher Guest’s folk music mockumentary A Mighty Wind and this thread (which

includes Julianne Moore and finds Christian Bale playing the Dylan character into his conversion to Christianity) is the weakest part of

the film and momentarily threatens to collapse Haynes’ delicate structure (it’s a very mannered, heavy-handed device much too

familiar to audiences to be taken seriously).

Other sections of the movie are mystical and poetic – drawing on Dylan’s influences and Haynes’ fascination with rebellion against

the constraints of rigid conservatism (a theme he also explored more literally in Far From Heaven). Dylan’s musical inspiration, folk

hero Woody Guthrie is envisioned in the person of a small African American boy (Marcus Carl Franklin) who hops freight cars and

totes around a beat up guitar until a black woman tells him to get with the times, prompting his switch to folk music activism. In

another segment Richard Gere plays the Wild West bandit Billy the Kid, whose individualism apparently inspired Dylan. Though the

link to Dylan isn’t clear it’s a beautifully filmed sequence that feels right.

The jigsaw puzzle approach of I’m Not There takes some getting used to and audiences steeped in traditional Hollywood structure are

going to probably find this non-linear film that leaves the moorings of traditional bio-pics far behind tough going. Plus, not all the

threads bind together (not that they’re actually meant to – that’s part of the point) but even with missteps (the mockumentary

segment with Bale and the stuff with the black kid in particular) Haynes takes you on a marvelous journey and its an intensely felt

picture that actually gets on the screen the enormous power that music in the hands of a genius can have on the world. There’s

never been a film quite like I’m Not There and even though it’s too long and gets a little too cow-eyed at times, Haynes’ unique

vision, the cinematic equivalent of the ultimate fan mail love letter, may be the precursor to an entirely new genre of poetic bio-pics.

That a potential new film genre has once again been initiated by a queer artist with the unique vision and tremendous gifts that

Haynes’ possesses isn’t a bit surprising. Want to see queer sensibility finely tuned to its height? Go see I’m Not There.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This Christmas, written and directed by Preston A. Whitmore II is standard issue holiday fare, Soul Food style in which Loretta

Devine presides over a family with lots of stereotypical problems returning to her California home at Christmas. I love Loretta

Devine, who should have gotten many more high profile movie roles after Waiting to Exhale (and plays a variation on that role here)

and am always happy to see her with another big screen part – even in a standard issue picture such as this. Regina King is the

oldest daughter who has taken on familial responsibility after the father left for good while Sharon Leal is the younger, beautiful and

selfish sister who went to New York for a modeling career. There’s an older brother on the lam from bookies, a younger brother who

is hiding the fact that he’s a talented vocalist, and a middle brother who is home for the holidays on leave from the Army and is

hiding a secret, too.

I’d forgotten that the trailer for the movie reveals the secret (he’s hooked up with a white woman) and was hoping things would get

interesting and that maybe he’d bring home his gay lover (talk about don’t ask/don’t tell!). But not a bit of it. All the characters

and their motivations are so stereotypical, in fact, that none of them really registers. On the plus side, inane as it is, at least this

isn’t one of those strident, slapstick white holiday movies – like Christmas with the Kranks – and also unlike its white counterparts, this

black holiday movie features gorgeous jazz versions of the Christmas standards and a sassy Soul Train line dance sequence (which

wears out its welcome, however, when Whitmore, who apparently loved it a lot, repeats it at the movie’s conclusion for a full five

minutes before rolling the credits).

Unique/Not So:

I'm Not There-This Christmas

Expanded Edition of 11-21-07 Windy City Times Knight at the Movies Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

I'm Not There-This Christmas

Expanded Edition of 11-21-07 Windy City Times Knight at the Movies Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.