Knight at the Movies ARCHIVES

Mommyism:

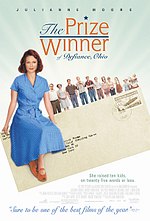

The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio and Flightplan

EXPANDED EDITION OF 9-28-05 Knight at the Movies column

by Richard Knight, Jr.

Julianne Moore has jumped in the time tunnel for another trip back to the 1950s. On the surface it seems that this

third cinematic venture by Moore to the Eisenhower era isn’t much different from Far From Heaven and The

Hours. In those films Moore played characters strapped into the binding fashions of the decade and the even more

stultifying culture based on surface appearances. Indeed, in The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio Moore

is a strapped in housewife again and this time, in addition to the constricting time period, she’s straddled with ten

kids and an alcoholic husband. But this time Moore’s character is based on a real person and here’s where truth is

stranger – and much more optimistic – than fiction. Evelyn Ryan might be horribly boxed in by circumstances but

her courage, grace, and cleverness time and again manage to save the day. Moore gives a masterful performance

filled with incredible nuance that is the main reason to see the movie.

Out screenwriter and first time feature director Jane Anderson has adapted the memoir of out writer Terry “Tuff”

Ryan. Ryan’s memoir, culled from her late mother’s carefully preserved notebooks, details the hundreds of jingle

writing contests that her mother entered and her incredible winning streak. The movie opens in 1956 in the midst

of the “describe our product in 25 words or less” contest craze when thousands of bored housewives vied for a

chance to win everything from a year’s supply of corn flakes to cars and trips. But Evelyn is no bored housewife.

She thrives on the chaos and the liveliness of her ten children and the stimulus offered by the brain teasers – and

she’s learned to find happiness within the confines of her life. This is tellingly illustrated when she wins big enough

to put a down payment on a house for the family and the bank loan officer and her husband Kelly (Woody

Harrelson) immediately decide that she doesn’t need to bother her pretty little head with the headache of home

ownership and don’t put her name on the deed.

More trouble comes as one of Kelly’s periodic alcoholic rages kicks in. We are shown unflinchingly that the family

has become used to this tyranny: while Kelly rants in the kitchen, steps away Evelyn and the kids are pointedly

ignoring him, watching television. When the abuse escalates and male authority figures are called on the scene

(policemen and a priest), Evelyn is seen as the one at fault for not trying hard enough. Evelyn just grits her teeth

and again accepts her fate.

As the incidents add up and Harrelson’s rages become larger, it becomes harder to understand Moore’s acquiesce

and downright perkiness in the face of such relentless verbal terror. Quick flashbacks don’t fully explain it either.

It would have helped to have been shown at least one scene where we see what attracted Moore and Harrelson to

begin with.

Harrelson, his hair dyed red to match Moore’s, is playing essentially a grown up baby bully, the weakest of

characters. He tries hard to add shadings but maybe they weren’t there to add. It’s hard for modern audiences to

understand, perhaps, the overbearing mentality of the 1950s male mindset. “It’s a depressingly masculine world,”

Judy Parfitt told Kathy Bates at one point in Dolores Clairborne and she might have been talking about the one

recreated in Prize, Winner as well.

Though Evelyn’s offhand observation to a neighbor, “I just have to sit down and have myself a happy cry” seems to

be the theme of the movie the unspoken sub-theme of “I hate men” runs throughout the picture as well. There’s

not a single flattering male character on screen. Evelyn is so constrained that she even has to take constant

sniping by the nasty milkman (when he finally softens at picture’s end it seems a real triumph for feminism – he’s

been enlightened at last!). And Evelyn and her fellow housewives (led by another prize winner, Laura Dern) are

careful to meet when it’s convenient for the men. It’s no surprise that Evelyn, who can’t drive and has waited

years to meet the group, finally gets to do so only after her daughter Tuff agrees to drive her.

When we finally get off with the girls it seems like not just the characters, but the audience, will be able to breathe

some free air at last. The dazzling, plastic fake world of sponsored contests adds a cheery respite but also

reinforces the lackluster terror of the everyday lives of the Ryan’s and gives the movie some much needed

breathing room, too. But it’s very hard to see Evelyn’s triumphs diminished time and again by Kelly’s rages. Ryan’

s real children, grown up, surround Moore at the conclusion of the picture and while reading of their grown up

accomplishments has the intended effect of allowing the audience to experience their triumph over adversity,

they've had years to shake off the after shocks. I didn’t feel the same clarity and peacefulness. At its core, Prize,

Winner is a feminist revenge picture without much wish fulfillment and I got the message loud and clear – in 25

words or less.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

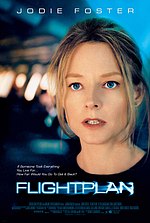

A smile from Jodie Foster has become as rare as hen’s teeth. As Flightplan begins her face is a road map of

unsmiling anxiety as she gets on a plane with her daughter. After nodding off she wakes to find her daughter

missing. Within minutes, Foster is back in Panic Room territory and once again, Hell hath no fury like a mother

whose child is being threatened. Though the plane’s the size of Detroit, the little girl couldn’t have gone far, right?

Well, yes and no…

Flightplan is a high concept thriller that speeds along at an agreeable pace, hitting on the audience’s fears – of

letting down your guard for a second where your kids are concerned, crazy people in public spaces, claustrophobia,

acting out in public, racial profiling, and authoritative indifference to personal tragedy. It’s all here – along with

plenty of melodramatic twists and turns – as Foster stops at nothing and I mean NOTHING – to find that kid. She’s

aided by gay friendly actor Peter Sarsgaard (sounding like he’s channeling John Malkovich) and a beautiful flight

crew headed by pilot Sean Bean and puffy lipped attendant Kate Beahan and Erika Christensen. Our actor John

Benjamin Hickey, alas, gets to play the dead husband in the casket.

Flightplan is a crafty little thriller, in spite of the huge leaps of believability required by the audience, and it’s

worth a trip to the Cineplex but don’t expect to come out smiling. Foster’s not going to discuss her private life,

she's not going to lighten up in her movies anytime soon (another thriller and a revenge picture have been

announced), and dammit, she’s not going to smile if she doesn’t feel like it either.

The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio and Flightplan

EXPANDED EDITION OF 9-28-05 Knight at the Movies column

by Richard Knight, Jr.

Julianne Moore has jumped in the time tunnel for another trip back to the 1950s. On the surface it seems that this

third cinematic venture by Moore to the Eisenhower era isn’t much different from Far From Heaven and The

Hours. In those films Moore played characters strapped into the binding fashions of the decade and the even more

stultifying culture based on surface appearances. Indeed, in The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio Moore

is a strapped in housewife again and this time, in addition to the constricting time period, she’s straddled with ten

kids and an alcoholic husband. But this time Moore’s character is based on a real person and here’s where truth is

stranger – and much more optimistic – than fiction. Evelyn Ryan might be horribly boxed in by circumstances but

her courage, grace, and cleverness time and again manage to save the day. Moore gives a masterful performance

filled with incredible nuance that is the main reason to see the movie.

Out screenwriter and first time feature director Jane Anderson has adapted the memoir of out writer Terry “Tuff”

Ryan. Ryan’s memoir, culled from her late mother’s carefully preserved notebooks, details the hundreds of jingle

writing contests that her mother entered and her incredible winning streak. The movie opens in 1956 in the midst

of the “describe our product in 25 words or less” contest craze when thousands of bored housewives vied for a

chance to win everything from a year’s supply of corn flakes to cars and trips. But Evelyn is no bored housewife.

She thrives on the chaos and the liveliness of her ten children and the stimulus offered by the brain teasers – and

she’s learned to find happiness within the confines of her life. This is tellingly illustrated when she wins big enough

to put a down payment on a house for the family and the bank loan officer and her husband Kelly (Woody

Harrelson) immediately decide that she doesn’t need to bother her pretty little head with the headache of home

ownership and don’t put her name on the deed.

More trouble comes as one of Kelly’s periodic alcoholic rages kicks in. We are shown unflinchingly that the family

has become used to this tyranny: while Kelly rants in the kitchen, steps away Evelyn and the kids are pointedly

ignoring him, watching television. When the abuse escalates and male authority figures are called on the scene

(policemen and a priest), Evelyn is seen as the one at fault for not trying hard enough. Evelyn just grits her teeth

and again accepts her fate.

As the incidents add up and Harrelson’s rages become larger, it becomes harder to understand Moore’s acquiesce

and downright perkiness in the face of such relentless verbal terror. Quick flashbacks don’t fully explain it either.

It would have helped to have been shown at least one scene where we see what attracted Moore and Harrelson to

begin with.

Harrelson, his hair dyed red to match Moore’s, is playing essentially a grown up baby bully, the weakest of

characters. He tries hard to add shadings but maybe they weren’t there to add. It’s hard for modern audiences to

understand, perhaps, the overbearing mentality of the 1950s male mindset. “It’s a depressingly masculine world,”

Judy Parfitt told Kathy Bates at one point in Dolores Clairborne and she might have been talking about the one

recreated in Prize, Winner as well.

Though Evelyn’s offhand observation to a neighbor, “I just have to sit down and have myself a happy cry” seems to

be the theme of the movie the unspoken sub-theme of “I hate men” runs throughout the picture as well. There’s

not a single flattering male character on screen. Evelyn is so constrained that she even has to take constant

sniping by the nasty milkman (when he finally softens at picture’s end it seems a real triumph for feminism – he’s

been enlightened at last!). And Evelyn and her fellow housewives (led by another prize winner, Laura Dern) are

careful to meet when it’s convenient for the men. It’s no surprise that Evelyn, who can’t drive and has waited

years to meet the group, finally gets to do so only after her daughter Tuff agrees to drive her.

When we finally get off with the girls it seems like not just the characters, but the audience, will be able to breathe

some free air at last. The dazzling, plastic fake world of sponsored contests adds a cheery respite but also

reinforces the lackluster terror of the everyday lives of the Ryan’s and gives the movie some much needed

breathing room, too. But it’s very hard to see Evelyn’s triumphs diminished time and again by Kelly’s rages. Ryan’

s real children, grown up, surround Moore at the conclusion of the picture and while reading of their grown up

accomplishments has the intended effect of allowing the audience to experience their triumph over adversity,

they've had years to shake off the after shocks. I didn’t feel the same clarity and peacefulness. At its core, Prize,

Winner is a feminist revenge picture without much wish fulfillment and I got the message loud and clear – in 25

words or less.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

A smile from Jodie Foster has become as rare as hen’s teeth. As Flightplan begins her face is a road map of

unsmiling anxiety as she gets on a plane with her daughter. After nodding off she wakes to find her daughter

missing. Within minutes, Foster is back in Panic Room territory and once again, Hell hath no fury like a mother

whose child is being threatened. Though the plane’s the size of Detroit, the little girl couldn’t have gone far, right?

Well, yes and no…

Flightplan is a high concept thriller that speeds along at an agreeable pace, hitting on the audience’s fears – of

letting down your guard for a second where your kids are concerned, crazy people in public spaces, claustrophobia,

acting out in public, racial profiling, and authoritative indifference to personal tragedy. It’s all here – along with

plenty of melodramatic twists and turns – as Foster stops at nothing and I mean NOTHING – to find that kid. She’s

aided by gay friendly actor Peter Sarsgaard (sounding like he’s channeling John Malkovich) and a beautiful flight

crew headed by pilot Sean Bean and puffy lipped attendant Kate Beahan and Erika Christensen. Our actor John

Benjamin Hickey, alas, gets to play the dead husband in the casket.

Flightplan is a crafty little thriller, in spite of the huge leaps of believability required by the audience, and it’s

worth a trip to the Cineplex but don’t expect to come out smiling. Foster’s not going to discuss her private life,

she's not going to lighten up in her movies anytime soon (another thriller and a revenge picture have been

announced), and dammit, she’s not going to smile if she doesn’t feel like it either.

Two motherhood movies: mother stands for comfort and mother as a force of nature