Knight at the Movies Archives

A documentary profile of Tony Kushner leaves one hungry for more while Clint Eastwood's poetic movie is just right

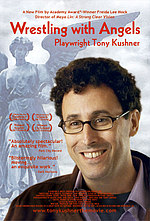

One might expect that playwright Tony Kushner, renowned not just for his angry, politically charged “Angels in America” and

outspoken AIDS activism might have the unapologetic wrath of his contemporary Larry Kramer. But based on the evidence in

Wrestling with Angels: Playwright Tony Kushner, the source of his fiery magnificence on the page and in interviews

remains a mystery. Freida Lee Mock’s feature length documentary about the famously gay writer shows us a great deal of Kushner

rushing about New York from project to project, enchanting audiences, both personal and professional, whenever called upon to

speak, and taking part in both public and private events (including his own commitment ceremony). But though it’s certainly fun to

get an insider view of Kushner’s world and excerpts from many of his plays are included as a bonus, Lee’s portrait seems to barely

scratch the surface of its celebrated subject. Worse, for the uninitiated, “Angels in America” gets short shrift.

The title of the film implies the opposite. The gigantic success, the incredible media phenomenon that “Angels In America” became

when it opened on Broadway in 1993 was indeed, one suspects, something for Kushner to “wrestle with.” “Angels” arrived at the

moment that America seemed finally, finally ready to deal – at least on the surface – with the AIDS crisis. So great was the

attendant fuss that everywhere one looked, it seemed, there was Kushner, an instant celebrity and gay hero for his outspoken

demands for gay rights in all areas, weighing in with his latest opinion piece or offering a sound bite on the latest issue. But the film

starts years after these events – apparently long after Kushner had learned to deal with the instant dual demands of celebrity and

spokesperson for the gay community. And though nothing that Kushner has produced since has had even close to the critical or

financial success of “Angels,” it’s not a topic the movie bothers to explore either.

Instead of “Wrestling with Angels,” we find that by the time Mock started filming – just after 9/11 when he was workshopping his play

about Afghanistan, “Homebody/Kabul” – that Kushner apparently had come to tame whatever demons had plagued him. This

Kushner is an easy going, quick witted charmer who moves quickly through the streets of Manhattan, the famous battle with his

weight having been conquered. And though he is heard to comment, “I find writing really difficult. You’re alone with your own weird

mind,” the revised pages seem to pour out as rehearsals progress on the play. When it doesn’t fare as well as Kushner had hoped,

he quickly moves on to the next project.

Likewise, when the film follows Kushner on a journey home for his father’s 80th birthday and segues into his biography, we quickly

glide over what made Tony Kushner TONY KUSHNER. The artistic and intellectual example of both Kushner’s parents is explored and

a discussion of their difficulty dealing with his homosexuality follows but again, not much of the passion that infuses Kushner’s work

is in evidence. Brecht is cited as an influence (not surprising) but this isn’t really explored and the writing of “Angels” could have

used a lot more screen time.

Kushner’s personal life is also skimmed over – though we see clips from his commitment ceremony to his partner Mark Harris,

there's no detail about the couple’s romance or their feelings on gay marriage. One learns more from the brief New York Times

announcement of the event (which occurred in May of 2003) and the personalities of Kushner and Harris (there’s even an activist

comment from Kushner about being aware of the danger of public affection between gay men) than is offered in Mock’s film. To be

fair, this may have been because Kushner’s partner Harris wasn’t comfortable being filmed (he’s not interviewed in the film).

The final section of the movie, however, does offer some fascinating moments of the playwright at work on “Caroline or Change” and

the more recent collaboration with Maurice Sendak, “Brundibar,” the infamous children’s opera that originally premiered at one of the

Nazi death camps. And we do get tantalizing moments – there’s a marvelous, all too brief segment in which Kushner, Kramer,

McNally, and Rudnick – the great gay playwrights – are interviewed by Frank Rich in a round table, for example. We also get a

persuasive Kushner volunteering in Florida in 2004 for Kerry during the election and finally Meryl Streep reading Kushner’s prayer for

AIDS. It’s a stunning moment that reminds one of the power of this great man’s words but makes one long for more insight into the

man himself. The film, which is being shown twice (January 12 and 16) in its Chicago premiere at the Gene Siskel Center is well

worth seeing. But those expecting an in-depth look at Kushner’s creative process and his importance within the theatrical community

and to American culture will have to wait for the next go round. www.siskelfilmcenter.com

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

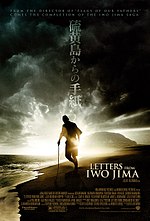

Letters from Iwo Jima is the follow-up of Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers. In Flags the director examined the manipulation

of the public at the end of World War II via the iconic photograph of a group of soldiers hoisting the flag on the tiny Japanese isle.

The movie intercuts between the bond drive the soldiers (a fetching group that includes Ryan Phillippe and Jesse Bradford) are sent

on and the bloody battle still raging back on the island. The movie’s point – the easy exploitation of a deeply patriotic and

sentimental public by calculating officials versus true but messy heroism – certainly resonates when one considers our current war in

Iraq and how we got there.

Letters, which sees the battle from the losing, Japanese point of view, has a very different feel. Desperate to hold off the

encroaching, enormous American fleet, everything hinges on their defense of Iwo Jima, yet even before the battle begins, the

Japanese know that they have no chance of winning. What ensues in this poetic, haunted film says much about the ultimate futility

of war. The powerful result, brutal and beautiful, may be Eastwood’s greatest film. Ken Watanabe heads a wonderful cast of

Japanese actors. Subtitled.

outspoken AIDS activism might have the unapologetic wrath of his contemporary Larry Kramer. But based on the evidence in

Wrestling with Angels: Playwright Tony Kushner, the source of his fiery magnificence on the page and in interviews

remains a mystery. Freida Lee Mock’s feature length documentary about the famously gay writer shows us a great deal of Kushner

rushing about New York from project to project, enchanting audiences, both personal and professional, whenever called upon to

speak, and taking part in both public and private events (including his own commitment ceremony). But though it’s certainly fun to

get an insider view of Kushner’s world and excerpts from many of his plays are included as a bonus, Lee’s portrait seems to barely

scratch the surface of its celebrated subject. Worse, for the uninitiated, “Angels in America” gets short shrift.

The title of the film implies the opposite. The gigantic success, the incredible media phenomenon that “Angels In America” became

when it opened on Broadway in 1993 was indeed, one suspects, something for Kushner to “wrestle with.” “Angels” arrived at the

moment that America seemed finally, finally ready to deal – at least on the surface – with the AIDS crisis. So great was the

attendant fuss that everywhere one looked, it seemed, there was Kushner, an instant celebrity and gay hero for his outspoken

demands for gay rights in all areas, weighing in with his latest opinion piece or offering a sound bite on the latest issue. But the film

starts years after these events – apparently long after Kushner had learned to deal with the instant dual demands of celebrity and

spokesperson for the gay community. And though nothing that Kushner has produced since has had even close to the critical or

financial success of “Angels,” it’s not a topic the movie bothers to explore either.

Instead of “Wrestling with Angels,” we find that by the time Mock started filming – just after 9/11 when he was workshopping his play

about Afghanistan, “Homebody/Kabul” – that Kushner apparently had come to tame whatever demons had plagued him. This

Kushner is an easy going, quick witted charmer who moves quickly through the streets of Manhattan, the famous battle with his

weight having been conquered. And though he is heard to comment, “I find writing really difficult. You’re alone with your own weird

mind,” the revised pages seem to pour out as rehearsals progress on the play. When it doesn’t fare as well as Kushner had hoped,

he quickly moves on to the next project.

Likewise, when the film follows Kushner on a journey home for his father’s 80th birthday and segues into his biography, we quickly

glide over what made Tony Kushner TONY KUSHNER. The artistic and intellectual example of both Kushner’s parents is explored and

a discussion of their difficulty dealing with his homosexuality follows but again, not much of the passion that infuses Kushner’s work

is in evidence. Brecht is cited as an influence (not surprising) but this isn’t really explored and the writing of “Angels” could have

used a lot more screen time.

Kushner’s personal life is also skimmed over – though we see clips from his commitment ceremony to his partner Mark Harris,

there's no detail about the couple’s romance or their feelings on gay marriage. One learns more from the brief New York Times

announcement of the event (which occurred in May of 2003) and the personalities of Kushner and Harris (there’s even an activist

comment from Kushner about being aware of the danger of public affection between gay men) than is offered in Mock’s film. To be

fair, this may have been because Kushner’s partner Harris wasn’t comfortable being filmed (he’s not interviewed in the film).

The final section of the movie, however, does offer some fascinating moments of the playwright at work on “Caroline or Change” and

the more recent collaboration with Maurice Sendak, “Brundibar,” the infamous children’s opera that originally premiered at one of the

Nazi death camps. And we do get tantalizing moments – there’s a marvelous, all too brief segment in which Kushner, Kramer,

McNally, and Rudnick – the great gay playwrights – are interviewed by Frank Rich in a round table, for example. We also get a

persuasive Kushner volunteering in Florida in 2004 for Kerry during the election and finally Meryl Streep reading Kushner’s prayer for

AIDS. It’s a stunning moment that reminds one of the power of this great man’s words but makes one long for more insight into the

man himself. The film, which is being shown twice (January 12 and 16) in its Chicago premiere at the Gene Siskel Center is well

worth seeing. But those expecting an in-depth look at Kushner’s creative process and his importance within the theatrical community

and to American culture will have to wait for the next go round. www.siskelfilmcenter.com

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Letters from Iwo Jima is the follow-up of Clint Eastwood’s Flags of Our Fathers. In Flags the director examined the manipulation

of the public at the end of World War II via the iconic photograph of a group of soldiers hoisting the flag on the tiny Japanese isle.

The movie intercuts between the bond drive the soldiers (a fetching group that includes Ryan Phillippe and Jesse Bradford) are sent

on and the bloody battle still raging back on the island. The movie’s point – the easy exploitation of a deeply patriotic and

sentimental public by calculating officials versus true but messy heroism – certainly resonates when one considers our current war in

Iraq and how we got there.

Letters, which sees the battle from the losing, Japanese point of view, has a very different feel. Desperate to hold off the

encroaching, enormous American fleet, everything hinges on their defense of Iwo Jima, yet even before the battle begins, the

Japanese know that they have no chance of winning. What ensues in this poetic, haunted film says much about the ultimate futility

of war. The powerful result, brutal and beautiful, may be Eastwood’s greatest film. Ken Watanabe heads a wonderful cast of

Japanese actors. Subtitled.

Not Great and Great:

Wrestling with Angels: Playwright Tony Kushner-Letters from Iwo Jima

EXPANDED EDITION of 1-10-07 Windy City Times Knight at the Movies Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.

Wrestling with Angels: Playwright Tony Kushner-Letters from Iwo Jima

EXPANDED EDITION of 1-10-07 Windy City Times Knight at the Movies Column

By Richard Knight, Jr.